Lessons Learned from Living More than Half a Lifetime Off-the-Grid

8 things I learned living off-the-grid

As of this year I will have lived more than half of my life off-the-grid.

I am not a conspiracy theorist, end of the world prepper, utopian dreamer or in the witness protection program. I'm just someone who thinks that getting my electricity from the sun, my water from the sky and my comfort from the natural temperature of the earth makes sense. Like most Americans I grew up in a conventional home, lived in conventional apartments as a young adult, and like most Americans I did not know how my electricity was being produced, where my water was coming from or how it would be treated after leaving the house. I didn’t know how my dwelling was built, what materials it was built from and their impact on the planet during their manufacture, installation and eventual disposal or breakdown. I had no clue that it could be built differently, better, more natural, more efficient.

I came to off-grid living through a series of chance events but it immediately resonated with thoughts I'd had since childhood, but had yet to put into words. The way we are currently living on this planet is fundamentally wrong and against nature. We are poisoning the air, water, and ourselves. Chopping down all the trees and killing all the animals. Modern houses are built crappily, from crappy materials, not made to last. Power plants are ugly and smell bad. The grid is an unattractive, dangerous, and inefficient jumble of wires and poles.

Humans lived for millenia without the grid. There has to be a better way for us to provide for our needs and satisfy our wants.

Living off-the-grid means freeing yourself from the wires and pipes that carry electricity, heating, cooling, and fresh water to your house and carry wastewater away from it. Living off-the-grid means still having a house that functions even when the power gets cut after a natural disaster, or because of a planned brownout, or any of the other myriad of reasons why the grid fails.

I've been heating and cooling my home naturally without backup, producing my own electricity, collecting my own water and treating my wastewater for more than half my life. It's been exciting, empowering, rewarding, financially-beneficial, and sometimes challenging and I've learned a few things along the way.

1. You don't have to drop out of society (unless you want to).

I have a bank account, pay taxes, drive a car and watch Netflix. I am not trying to escape from the "real world". I don't have a stash of MREs or a "bug out bag". The stereotypes about the "kind of people" who live off the grid are pervasive. The media loves these stereotypes because they make good entertainment: the smelly hippie, the tortured loner, the militant survivalist, the brainwashed cult follower. Where do we see depictions of happy, healthy, lucid individuals and families choosing not to connect to Big Power, Big Oil, and city water? Living off-the-grid is not about sacrifice, deprivation and hardship. It is about common sense, technology and hope. It's about living a comfortable, "normal" life without continuing to plunder the earth.

Living off-grid can by definition be a little isolating because the places where these types of homes are currently allowed to be built tend to be more rural, on the outskirts of smaller towns and communities. After living in a major city for many years, I first found this difficult and felt like I was "missing out" on "the action" but now that I'm acclimated to small town life, I wouldn't trade it. I sometimes feel like I'm looking at the world from the bottom of the sea. The rest of the world is on the surface of the sea as viewed from fathoms deep. I can see light, shapes and colors, and even hear noises, but everything is muted, soft-focus. Everything but the stark urgency of the climate crisis. That blares in my skull and creeps over my skin. The only way to calm myself is to keep searching for, living in, and sharing solutions.

There is a disconnect from the "real world" in Taos that can happen when you live there for a while. Fashions come and go. National news stories flutter by. But the land and the sky, the wind and the sweet, baked smell of sagebrush, the extremes of temperature, the chores of frontier living, these all are in the foreground.

The internet has been hugely beneficial for off-grid homesteaders and communities. There are critics who complain about the "cognitive dissonance" of living off-grid while being connected to WiFi. How else do we share our stories? I feel like, if a beautiful alternative to the current self-destructive path we are on exists but no one knows about it, what's the point of all of our hard work? The internet has allowed individuals and groups to share their experiences and knowledge, connecting with others off-grid and blazing trails for more people to follow.

2. Humans are adaptable. Get out of your "comfort zone".

Modern houses are designed to put you in the "comfort zone" when it comes to temperature, around 72 degrees, day in day out, any season, any climate in any type of building. Conventional homes don't magically maintain a comfortable temperature by themselves, you have to heat and cool them, mostly by burning fossil fuels for electric heat or directly burning fuels like wood, heating oil or natural gas. When living in a conventional home, I didn't really give this too much thought. I took it for granted that this is just "the way things are '' and that I'd always have some kind of heater or AC and a utility bill to go with it.

Living off-the-grid in a home designed to heat and cool itself naturally, I've learned to pay more attention to the operation of the house, close the thermal shades at night to keep the heat in, correct any cold air drafts, operate the windows and skylights to cool off the house in the summer. My house does not stay 72 degrees year round, no matter what the weather. It varies between 60 and 78 degrees, for me a little chilly and a little too warm. But I've learned to adapt, with a big fleece robe and fluffy comforter for the winter, and an electric fan and icy drinks in the summer. And it's certainly a matter of relativity. When it's 10 below zero outside, 60 is practically tropical. When it's 101 outside, 78 is blissfully cool. If you think about all the different climates humans have called home around the globe, you realize that we are highly adaptable as a species and the "comfort zone" is much wider that a homeostatic 72 degrees. That is not to say that you can't achieve the comfort zone in an off-grid home and many newer buildings do so through design or back-up systems. But if you reach outside your "comfort zone" you can build more affordably and in more climates.

3. Something isn't precious until you are responsible for it.

In the "modern", "developed" world we have been riding the wave of cheap, available fossil fuel for over 100 years. It has transformed industry, transportation, agriculture, housing, and virtually every other aspect of life. "Power" is just as much a belief system as an economic system, so huge, so pervasive, as to become almost invisible. Most people in the "modern" world don't chop wood for heat, burn cow dung for cooking, haul fresh water on foot from miles away, or sit quietly in the dark after the sun goes down. "We" have frothing Jacuzzi bathtubs, giant monolithic refrigerators with built in cameras and led monitors, we have cheap gasoline, cheap junk food, cheap clothes, blazing bright, glittering metropolises, where you can feel the heat from the glow on your face at night, we poop in drinking water, throw away 1/3 of our perfectly good, uneaten food. We have hot and cold water at our fingertips, we flip a switch, press a button, or program an app and our homes come roaring to life. We pay for it. We expect it. We expect to pay for it. Pervasive and invisible.

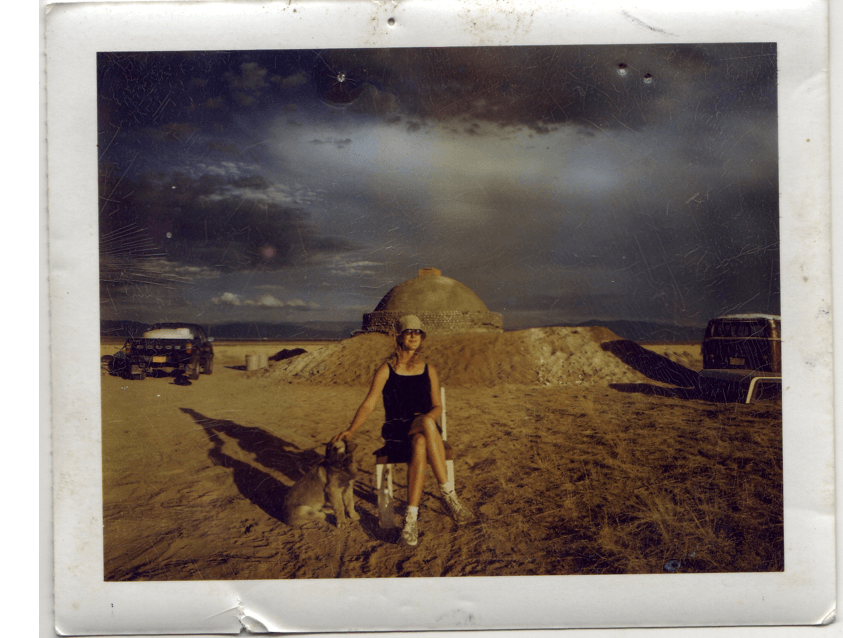

Living off-the-grid forced me, for the first time in my life, to think about where my resources come from, how they are manufactured and how I use them. As I built my own house, starting with and living what now might be called a Tiny Home, a 120 square foot earthen and plaster dome, I lived for a time a lifestyle closer to most people in the majority world: no electricity, no running water, a pit toilet outside. As my project progressed I slowly could afford, and add amenities. My electric system started as one solar panel, 2 batteries, a charge controller, a DC outlet and one lightbulb. My first solar-powered light bulb was a revelation. After living for months with no lights after dark, struggling to read and function at night by candle, headlamp and lantern light, the illumination from one bare bulb in my tiny hut was tranformative, thrilling. Not only could I cook, clean, read and relax without fumbling around in the semi-dark, I was giddy just knowing that the energy was coming from a clean and renewable source. I had harnessed my little fraction of the energy that hits the earth each day and put it use. It was mine for free and forever.

4. If you learn how to work WITH the abundance of nature, it will provide more than you need.

Any off-grid electric system, no matter the size, requires the respect and engagement of the owner/operator. You must live with an awareness of the limits of your system. You must design your home to be as efficient as possible. You must consider the seasons and the weather, how many cloudy days you've had in a row. Your electricity isn't a seemingly unlimited resource being produced elsewhere, in someone else's backyard, rather it is collected and stored in your system, for your exclusive storage and use. If you leave every light in the house on all night and do 10 loads of laundry and run your blender for 5 hours and binge-watch the Great British Baking Show on your 50" TV, after 3 days of cloudy weather, you're probably going to run out (temporarily) of electricity. If, on the other hand, you choose awareness, engagement and respect, you will never run out of electricity and will feel especially smug when the grid power in the area goes out and your town and neighbors are now the ones sitting around in the dark and fumbling with candles.

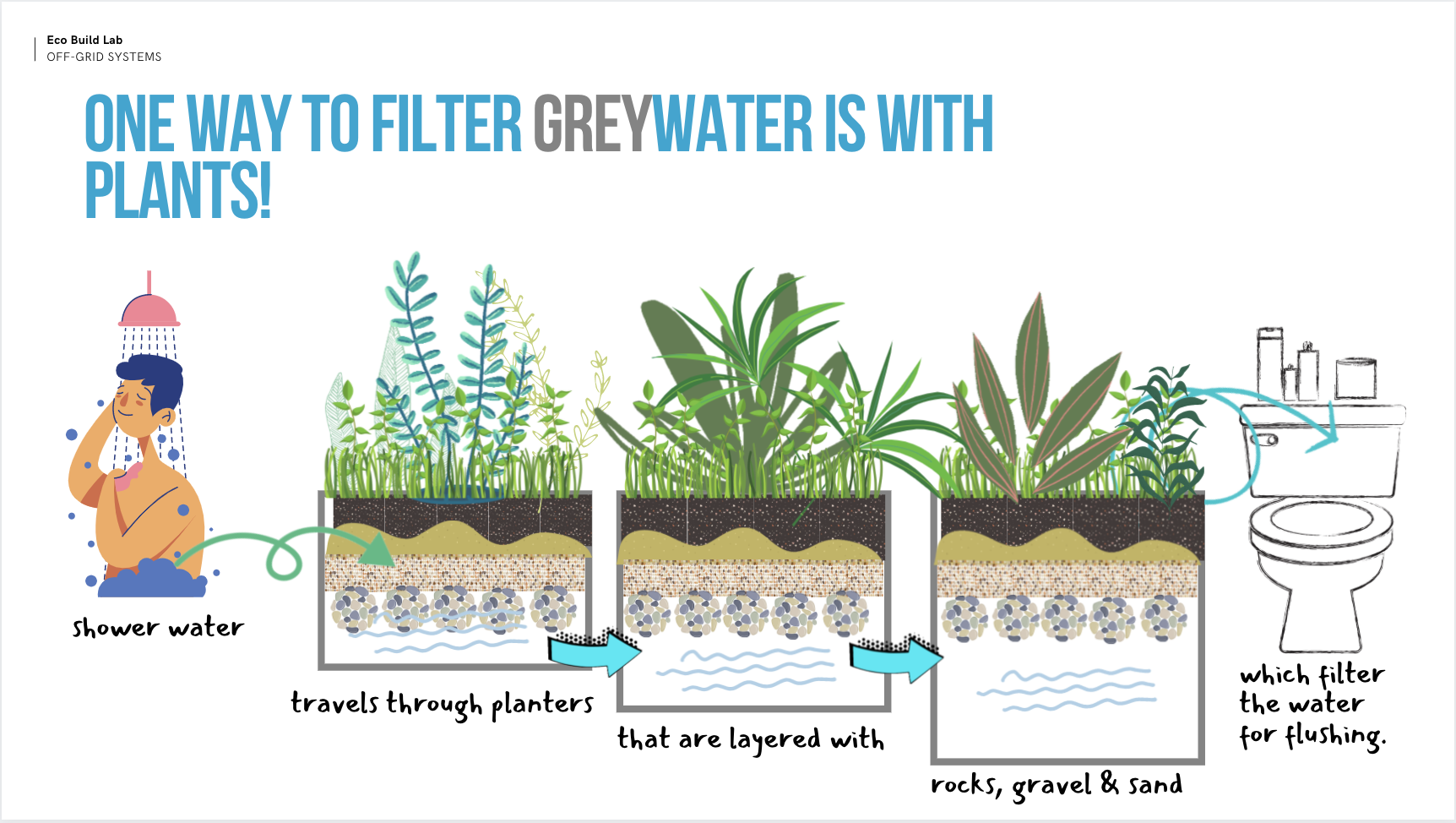

The same holds true for water. If you are choosing to live strictly off water collected off your roof from rain and snow, you are going to have a very different relationship to water. You are going to design your building for maximum water efficiency, hopefully installing systems to reuse and treat every drop more than once. You are going to choose the most efficient appliances. You won't absentmindedly leave the tap running. If you notice that you have a leaking fixture you're going to fix it immediately. You're going to check the water levels in your storage tank, monitor your usage, consider the seasons, watch the weather forecast, consider when to shower and when you can splurge on a bath, assess how many loads of laundry you can do.

5. You can

align your daily life with your values.

So much of being seen as "green", " eco-friendly" or "sustainable" these days has been commodified and greenwashed to the point that driving a new $100,000 Tesla, paying to do a carbon offset for your flight to Europe, sporting a $50 metal drinking water bottle, covering your roof with tens of thousands of dollars of solar panels while tying in to the electric grid, are ways of expressing your ethics through conscious consumerism. All these choices are better than driving a gas guzzling SUV, flying with abandon, quenching your thirst with bottled water, or burning coal to produce all your electricity. If you have the money these choices are all very easy and comfortable, sexy even, especially since they do not challenge our consumerist culture.

But what if your daily life, including just spending a day in your most comfy sweatpants binging a new series, in and of itself was reducing the strain on our environment and resources? Would knowing that when you turn on the lights you are no longer burning fuels feel good? Would showering in solar heated, filtered rainwater that you collected from your roof help you feel like you've done your part to reduce strain on our dwindling freshwater resources? How amazing would it be to know that heating your house with the sun isn't putting any additional power (or money) in the hands of warmongering despots and morally bankrupt fossil fuel corporations?

Though I've lived so long off-the-grid that feeling good about my lifestyle is something that's just normal everyday life, recent world events have given me fresh eyes and renewed zeal about my choices.

6. There is no such thing as perfectly "green".

It seems that when you make a concerted effort to live a more eco-friendly life, some friends and acquaintances feel entitled to cross-examine your lifestyle, pointing out perceived contradictions. "Well, you still drive a CAR!" "But you get your food from the GROCERY STORE." "That pen is made out of PLASTIC." Well, yes, if I could live off-the-grid in a walkable green city and purchase all my food from a local organic farm and buy artisanal fountain pens made from sustainably harvested vegan feathers, yes, of course I would. But I don't live in utopia, yet, and I am choosing what I believe is the best path available to me at this time. Sometimes you need to spell it out for people, "Please support my efforts by not constantly pointing out where they are (in your mind) lacking or even contradictory".

7. "They" don't make it easy.

It is not the easiest thing in the world to finance and build an off-grid home that will receive an official certificate of occupancy and be eligible for homeowners’ insurance. All these systems, county planning, the mortgage and insurance industries are inherently biased towards conventional construction and utilities. Even selling a perfectly functioning, beautiful off-grid home can be challenging with realtors and appraisers who are not familiar with them and the lack of "comps", comparable homes in the area.

I wouldn't say a conspiracy exists against off-grid and alternative construction but it is rare to find municipalities that are taking the time to understand and validate these approaches. Taos, New Mexico is one of the rare exceptions and I feel thankful to live here.

8. I want to help make off-grid living more accessible for everyone.

I want to share the benefits, drawbacks and victories that off-grid life provides. I want to help people understand the systems that support this type of existence. I want to help people decide if this is right for them. I want to share mistakes so you don't have to make them. I want to continue to learn about all the different ways to live off-grid and share success stories from all over the world. I want to build a supportive community where we share knowledge, inspiration and the latest technology.

Actually, I AM doing these things right now, from my solar powered computer in the comfort and quiet of my off-grid home.

Yes, that's a different house from the other photos. It's also off-the-grid.

SUBSCRIBE

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.

SUBSCRIBE

Thank you for contacting Eco Build Lab.

You will be hearing from us in your inbox!

Please try again later.